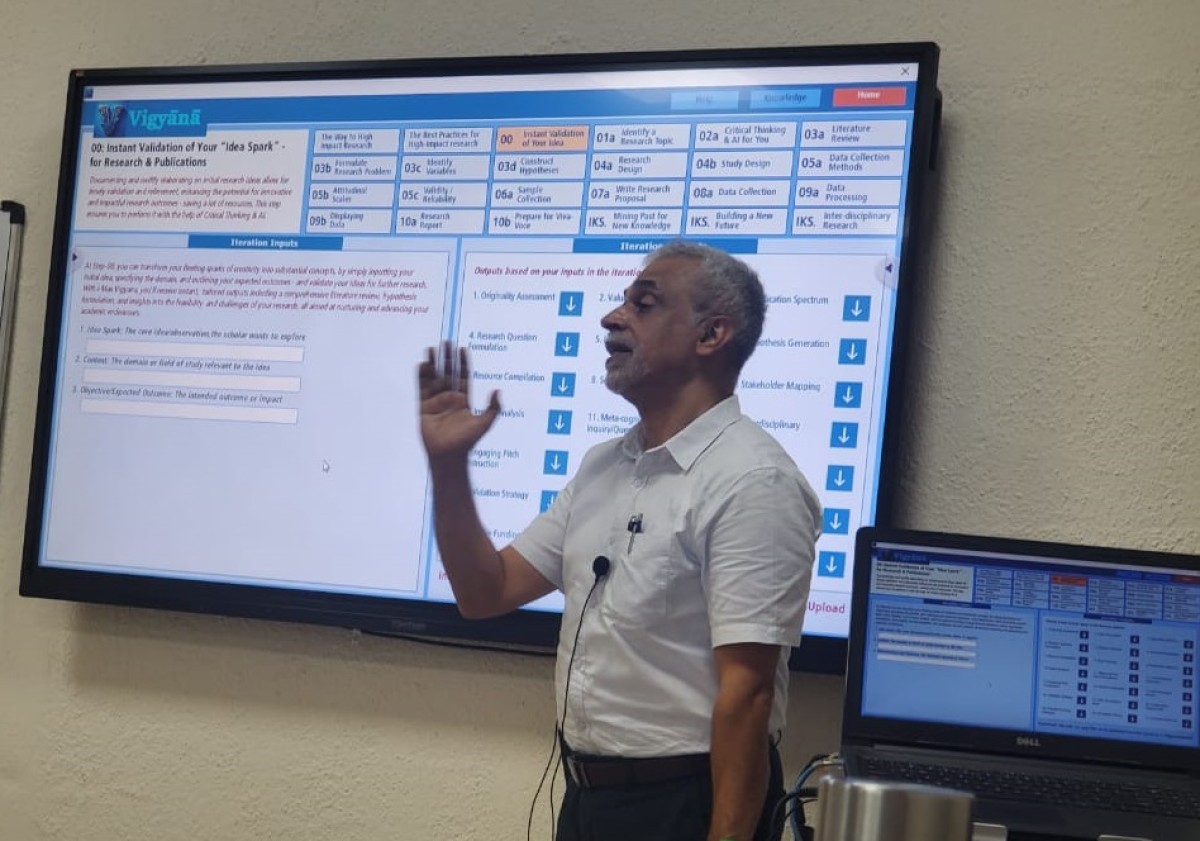

Espior founder Suresh Namboothiri briefs teachers at an IMG event in Trivandrum. Photo:TikTalk Newsletter

Doing research is tough, especially in India, where you have to spend years on it as everything is laborious, right from choosing the research subject. Months are spent defining the problem, reviewing the literature, and establishing the model before one can even start work on the actual project.

Espior Technologies, which offers solutions to revamp Indian engineering education, has introduced a new AI product to assist researchers and their guides on the path to a PhD. The model is tailored to address the needs of Indian scholars and aims to create high-impact research, says Suresh Namboothiri, founder of the Pune-based firm.

As the Chief Operating Officer at Tata Motors (1998 to 2005) and the leader of BPL Sanyo's product development (1987 to 1998), Namboothiri traversed different domains during his three-decade-long journey in the industry before turning his attention to academics in 2005.

The 62-year-old says that during his tenure at top Indian companies, he interviewed tens of thousands of engineers and became increasingly concerned about the quality of education and research in the country.

This concern was shared by a network of friends he gathered worldwide during his industry tenure. When Namboothiri decided to establish a company for education reform, many of them offered help.

Inputs came from 158 experts worldwide, leading Espior to develop an exhaustive list of modules that cover every branch of engineering. The firm also utilised the latest large language models (LLMs) to develop these modules. The quest to find true solutions for the real Indian problems led to about fourteen educational innovations – like what the company says is the world’s first and only professional interview simulator, professional interview trainer etc.

“We were one of the first companies in India to approach OpenAI and buy their APIs to integrate into our products,” says Namboothiri.

The latest product, Vigyana, offers an AI-assisted model for research scholars and guides. During a demonstration of the product, organised by the Institute of Management in Government in Trivandrum, Namboothiri said that all stages cater to Indian conditions.

From the Kothari Commission, the first comprehensive review of the Indian education sector after independence, to the latest National Education Policy, the importance of critical thinking in research methodology has been emphasised. However, no Indian education system has developed a syllabus on critical thinking.

Another element Espior focused on was research methodology. In centres of educational excellence in India and abroad, research methodology is taught by math teachers as it involves statistics – that is an injustice to the true spirit of research.

“These two key things were taken into account when developing Vigyana,” says Namboothiri. “The model offers assistance at every stage of the research, from forming the research question to an AI-assisted viva-voce model.”

Unlike most AI models entering the market, Espior’s curriculum development work, which started 15 years ago, has helped train its AI models with Indian data.

“We started the research in 2007 and covered the length and breadth of the country, from Marthandam in Tamil Nadu to Sundar Nagar in Jammu, from Kutch in Gujarat to Dibrugarh in Assam. I visited over 250 learning centres, like universities, to collect data and develop engineering curriculums relevant to India.”

It was a painstaking effort that involved significant financial commitment. “I sold three of my ancestral properties in Kottayam to raise 4 crore rupees to enable this,” says Namboothiri.

But he downplays this, noting that over a dozen people invested crores to raise the 17 crore rupees needed for the venture. “Some of them had not even been to India but believed in the cause and were willing to back the project.”

They all wanted to develop an educational system relevant to the times and believed India was the best place to try this. Once proven in India, this can be replicated in a dozen countries.

Espior’s work led to the establishment of India to the Max, aimed at enabling a future where Indians conceive and develop finished products in India. “i-Max is a movement to strengthen the concept of real engineering in the Indian engineering educational system – by working at its fundamentals,” it says.

Still, what they have achieved so far is akin to reaching the base camp. A much tougher climb lies ahead – convincing education policymakers.

As the ecosystem is shaped and run by products of the very system that Espior is trying to disrupt, the resistance comes at several levels.

Even financiers who focus on Edtech are locked into startups that help students with competitive exams like UPSC, and a revamp of the education model is not their cup of tea.

Unlike the West or China, private endowments that provide millions to universities and research institutions are almost absent in India, though we have churned out successful companies that have raked in billions, especially after the IT boom.

“We are in a sector that does not exist yet. Our aim is to build cognitive rigour, and that is not included in the capitalist's definition of Edtech,” says Namboothiri.

The success of India’s software industry has made the re-engineering of the education sector even more challenging.

The software services that major Indian companies provide are more akin to clerical excellence than actual innovation, as there is little emphasis on product development. However, these services bring in millions of dollars and attract top talent.

Namboothiri draws a parallel to the colonial era’s Macaulay-influenced education, which made knowledge of English a key to success under British rule. Becoming English-speaking civil servant was an aspiration as it was seen as a ticket to prosperity. Now, coding skills have replaced it.

This ecosystem is forcing those with talents in other areas to set aside their abilities and learn coding to land cushy jobs. Policymakers also encourage such an ecosystem to churn out similar success stories.

As a result, students in disciplines like chemical or electrical engineering are urged to learn coding skills to get employed in the software sector. JavaScript and Python have become the keys to placements, and engineering colleges now measure their success by campus recruitment numbers.

On the other hand, the current education system fails to invoke interest in students’ chosen subjects. Added to that is the pressure from family and friends to adopt financially rewarding careers and leave their passions behind.

Building a new ecosystem where the innate passion of students is nurtured and tutors are equipped with the right tools to guide them may sound like an idyllic dream. But that is something that Namboothiri can relate to.

As a much sought-after expert in pedagogy, or the art and science of teaching, he had realised the importance of teachers long ago.

During his student days, Namboothiri never envisioned himself as an engineer and was inclined to become a cameraman and enter the movie world due to his talent in writing and painting.

However, his father forced him to pick engineering, so he joined Palakkad Engineering College. Namboothiri admits that he rebelled mentally and neglected his studies.

His poor performance in exams startled Mechanical Engineering Professor Dr. KK Padmanabhan. One day, he took Namboothiri out of the class, led him to a well-maintained old Ford car parked on the campus, and asked, “Is this a piece of art or a piece of machinery?”

“I said this is a blend of both,” Namboothiri recalls.

Then the teacher told him: “This is your career. You are already an artist. Now learn engineering and blend both. The Taj Mahal is attractive because of its artistic excellence, but it is sustained due to engineering.”

This encounter changed Namboothiri's course, and he went on to become one of the top finishers in his engineering degree.

He says every successful person will have a similar tale, that of one teacher who inspired them or showed them the right direction.

Espior’s mission now is to transform engineering institutions into places of innovation through modern curriculum, lift the standard of research, and motivate teachers to be that ‘One Teacher’ who moulds successful engineers.

As the Indian education sector itself is looking for that elusive spark, Namboothiri may well be the teacher who can provide it.

Google too makes a beeline to TN

Tamil Nadu continues to woo big-ticket investors, with Google now saying they will start manufacturing its high-end Pixel phones in the state. According to BBC, the phones will be made at the Foxconn factory in the state and will hit the market this year. Additionally, Google will also establish a factory in Tamil Nadu to manufacture drones.

At this rate, Tamil Nadu could easily achieve its desired target of becoming an economy of 1 trillion US by 2030. Foxconn and Pegatron already assemble iPhones in the state. The Economic Times estimates that 80 percent of the 14 billion US dollars worth of iPhones assembled in India come from Tamil Nadu factories.

A chicks to riches story

We at TikTalk get excited when we come across innovative firms that solve problems confronting all of us. Rajasthan-based Golden Feathers is such a venture. The company turns chicken feathers into yarn and paper, trains tribal women to do the work, and now generates 1.12 crore rupees annually. The company’s founder, Radhesh Agrahari, tells 30 Stades that it has upscaled 600 tonnes of chicken waste into handloom cloth (wool) and handmade paper since 2019. With stalls selling chicken fries popping up everywhere in Kerala, imagine how many tonnes of chicken feathers end up in our landfills!

A nudge from your app

We are all guilty of this: installing apps and never using them again. According to one study, the average millennial has 67 apps on their phone, but regularly uses only 25. Now Google is trying to bring those buried apps on your phone back to your life by using widgets, reports TechCrunch. For example, tapping on an image of sneakers would bring the Android user to a page in a shopping app where they could complete the purchase, says the report. Not good news if you are an online shopping junkie.

Typos of the world unite

Autocorrect is very helpful but can be a pain in the neck when it starts changing words that it is not familiar with. Apparently in Britain, names from India, Wales, and Ireland get changed often as the English dictionary does not recognise them. Indian names like Savan get changed to Satan, Rashmi to Sushi, and Dhruti to Dirty or Dorito, says a report in The Guardian. So the affected people have started #I-am-not-a-typo campaign and want tech companies to do more to solve this problem.