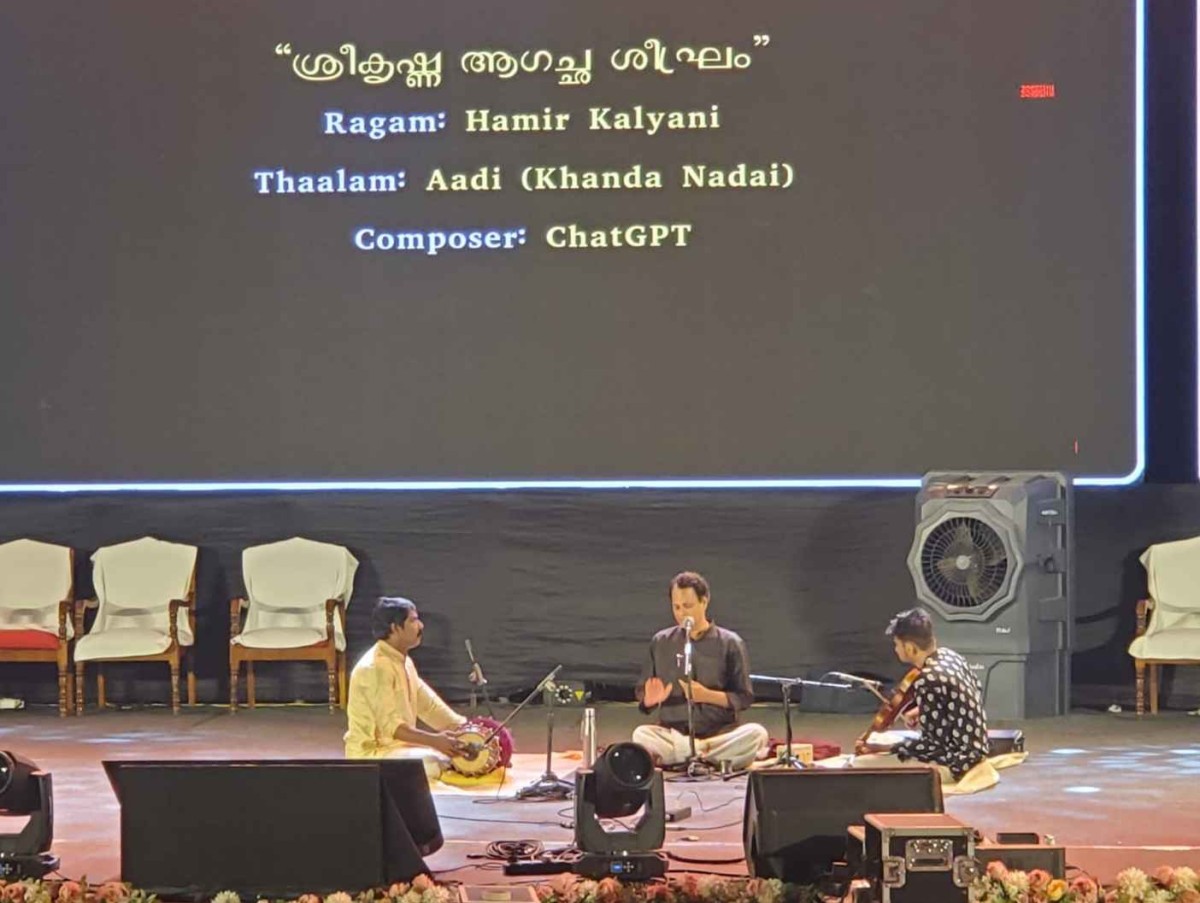

Achuthsankar S Nair rendering a Carnatic Keertana written in Sanskrit by ChatGPT. Photo: TikTalk News

As debates about artificial intelligence continue to swing between hype and alarm, Achuthsankar S Nair, a musicologist and an Indian academic with decades of experience in AI and bioinformatics, offers a challenging way to assess AI capabilities: through fine arts.

“AI has started to capture the essence of aesthetics, of humanity, of human society, of different cultures,” says the former director of the Centre for Development of Imaging Technology in Kerala. “So the achievements of AI in arts and fine arts are what should truly astonish us. That is what should remind us that AI has reached a very great height.”

Those who dismiss AI as “just pattern matching algorithms,”Achuthsankar suggests, fundamentally misunderstand what aesthetic creation requires. In his view, intelligence reveals itself most clearly not in logic or efficiency, but in domains shaped by taste, culture, and emotional resonance developed by humans over the centuries.

“It is fine arts that provide the best benchmark to test the intelligence of AI,” he said during a demonstration concert recently, during which he presented keertanas created by ChatGPT. “That is where we can recognise it as something we need to respect and acknowledge.”

Vocal Evidence: The composition was unusual: Carnatic music keertanas whose Sanskrit lyrics were generated by ChatGPT, following the traditional structure of devotional songs in praise of Ganesha.

“We usually say Tyagaraja composition, Swati Tirunalkriti, and so on,” he explains. “But this is a ChatGPT creation. That's the only difference.”

He composed the melody himself in the raga Hamsanandi, set to Adi tala, using the AI generated lyrics. His challenge to listeners: “Forget for a moment that ChatGPT wrote it, and listen to it as if you were hearing a composition in a Carnatic music concert. Form your opinion that way.”

The lyrics preserved rhyme and meaning. The result, he suggests, was structurally indistinguishable from traditional compositions. The melody required human intervention, but rather than seeing this as AI’s limitation, he views it as evidence of a fundamental shift in how creative work happens.

“We are going to coexist with AI,” he said. “We are going to do things together with AI at several levels as we go ahead.”

Poetic Progress: The evolution has been rapid. Five years ago, he notes, machine translation of poetry was crude and mechanical. “If you gave a Malayalam poem and asked it to translate it into English and back, the result was very unpoetic.”

Now the behaviour is strikingly different. “If you give an old Malayalam film song, it now provides more than one translation. It understands that it is a poem and that it needs to be translated poetically. It will give you the meaning of the lyrics, but also suggest alternative poetic renderings.”

“What I am hinting at is that AI is reaching a level where it can appreciate and reproduce the highest level of aesthetic sense of human beings.”

Complex Patterns: This is where his technical knowledge and music background becomes key to his argument. Fine arts involve extraordinarily complex patterns: cultural context, emotional resonance, structural rules, improvisation within constraints. Indian classical music alone presents a formidable challenge.

“Our music is complicated. Our notes are not straight. They sway rather than holding steady like Western do-re-mi. That is the cultivated aesthetic beauty of India. It is an acquired taste. And AI has already imbibed it.”

He contrasts this with Western symphonic music, where orchestral parts are precisely notated and performers follow the score closely. In Indian classical music, ragas define boundaries within which performers improvise extensively. The same composition by the same artist can vary substantially each time. Improvisation is fundamental to the form itself, not an occasional feature.

When AI can engage meaningfully with these patterns (not just reproduce them mechanically but respond, vary, and create within their constraints) that demonstrates intelligence of a high order, he argues. The fact that it happens through pattern recognition doesn’t diminish it. It reveals that pattern recognition at sufficient depth is a form of aesthetic intelligence.

Listens and Responds: But his most compelling evidence comes from real-time musical interaction. He points to work by Raghavasimhan Sankaranarayanan, an Indian origin PhD student at Georgia Tech who has built an AI controlled robotic violinist trained in Carnatic music. Sankaranarayanan brings both engineering expertise and a background in Indian classical violin to the project.

In a video clip Achuthsankar played during the concert, the robot doesn’t merely play back scores. When Sankaranarayanan prompts it musically, it follows the Sankarabharanam raga, responds in real time, and introduces variations. It behaves less like playback and more like a musical conversation partner.

“The great thing about ChatGPT, or AI systems like this, is that they are also able to receive a prompt in music and reply with music,” he says, emphasizing how this differs from earlier computer music systems that could only execute predetermined sequences.

The Authorship Question: This naturally raises uncomfortable questions. Last year, as Nobel Prizes were announced, a joke circulated online: might the Literature Prize soon go to AI? The idea feels absurd, but he asks why.

“The value of a book is created in the mind of the reader. As they say, every reading produces a new text,” he said. “One can argue that the creator had no feelings or no real-life experience. But how do we know whether a human writer who produced a similar work actually had those feelings?”

Humans too can fake emotions, he points out, citing scammers who use romance to cheat victims. “A human being can pretend to have feelings and still create a poem or a book. AI is no different. It has no feelings, but it can impress upon you that it has emotion and intention. In both cases, those things are actually non-existent.”

He also stresses that AI creation is never solitary. “Every piece of text produced by ChatGPT is actually a combined effort of human beings and ChatGPT. It is always a response to a prompt.”

A Different Lens: His argument is neither celebration nor alarm. It’s a reframing: if machines can participate meaningfully in art (domains shaped entirely by cultivated taste, cultural knowledge, and emotional resonance) then dismissing them as incapable of “real” creativity reveals more about our assumptions than about their capabilities.

Not because AI feels. But because, increasingly, what it creates demonstrates the kind of intelligence we’ve long considered uniquely human, he argues. And in Achuthsankar’s view, those who understand both the technical mechanisms and the aesthetic demands are often the most impressed, not the least.

Trivandrum innovations step out

Kerala quietly logged a double win in research commercialisation last week, with CSIR – National Institute for Interdisciplinary Science and Technology (NIIST) unveiling a system that converts pathogenic biomedical waste into value-added soil additives, eliminating the need for energy-intensive incineration. The rig safely processes medical waste while neutralising odour and leaving behind manure. Developed in collaboration with Angamaly-based startup Bio Vastum Solutions, the technology can process biomedical waste into soil substitutes quickly through a five-stage process that ensures complete disinfection. Independent studies by ICAR and agricultural universities have validated the safety and quality of the output. The technology has been used and validated at AIIMS, New Delhi.

The second breakthrough comes from the Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology (SCTIMST). The world’s first tissue graft scaffold made from the gall bladder of farm animals has now entered the market. It was developed by Dr T V Anil Kumar and his team at SCTIMST. The technology was transferred in 2017 to Alicorn Medical, a startup incubated at the institute. Marketed as CholeDermR, the product received Class D approval from the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation in 2023 and has shown promising results in treating chronic diabetic foot and leprosy ulcers, some persisting for over a decade. Institute director Dr Sanjay Behari says the platform could potentially be extended to create more such products for global export.

Japan to allow UPI payments

India’s UPI is steadily expanding to more countries, with Japan now exploring its adoption to serve a growing base of Indian tourists. When Indian tourists in Japan use UPI for payments, their bank accounts in India will be debited. Japanese IT services company NTT Data is partnering with the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) to enable acceptance of the payments system in Japan on a trial basis in fiscal year 2026. Launched in 2016, UPI processed 185.8 billion transactions in fiscal year 2024, a 42 per cent jump from the previous year, according to NPCI. Nearly half of all global instant-payment transactions in 2023 ran through the system, and the IMF has since described UPI as the world’s largest real-time payment network.

1,000 Ashes, one CubeSat

A former Nasa and Blue Origin engineer is betting that space memorials need not remain the exclusive preserve of the wealthy. Ryan Mitchell’s startup, Space Beyond, plans to send the ashes of up to 1,000 people into orbit aboard a single CubeSat on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rideshare mission scheduled for October 2027. Memorial spaceflights have existed since the 1990s but have typically come at a high cost. Space Beyond says prices will start at 249 US dollars, opening up orbital memorials to customers without deep pockets.

Brush with a smart cow

Veronika, a Swiss Brown cow in Austria, is now a star subject. Researchers observed her using a brush to scratch herself, switching ends and adjusting technique depending on which part of her body needed relief. Animal intelligence specialists say this counts as flexible, multi-purpose tool use, a behaviour previously documented convincingly only in humans and chimpanzees. For now, as this BBC video shows, Veronika remains unconcerned about the academic implications. She just knows what works – and is milking the attention.