The cluster of Lakshadweep Islands is like an unsinkable aircraft carrier for India. Handout image

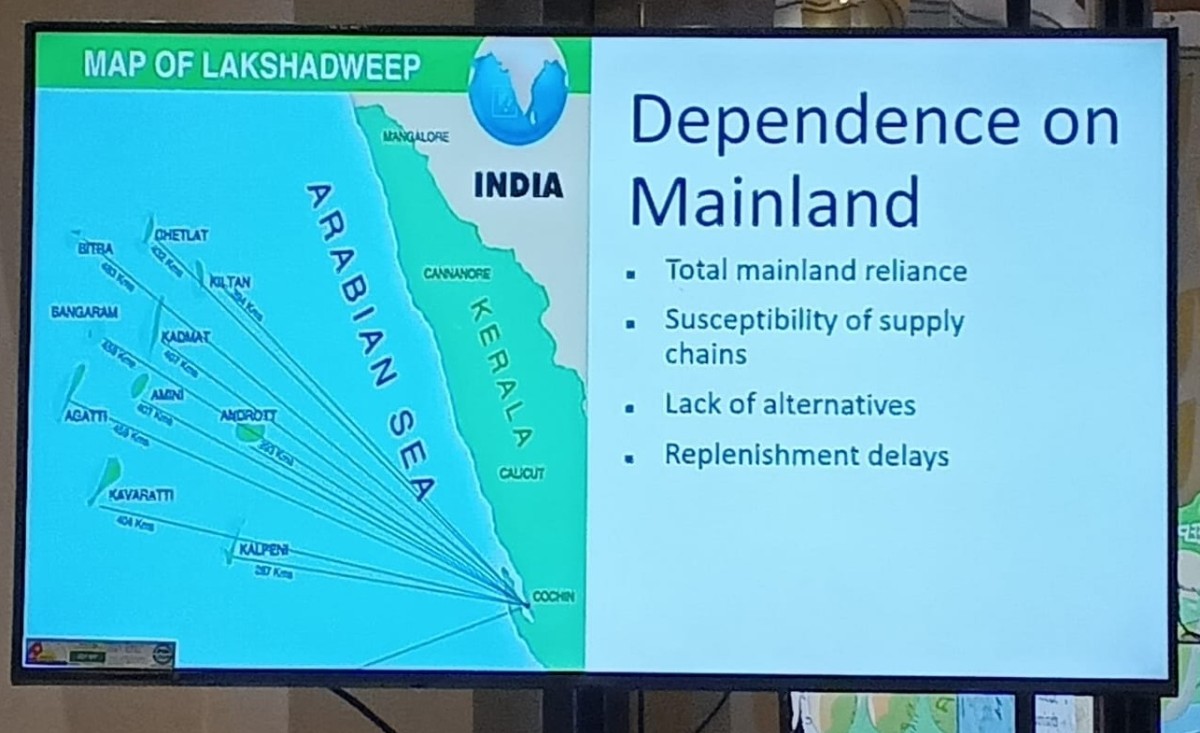

When you think of the Lakshadweep Islands, it’s usually picturesque boat trips that come to mind for most Indians. Yet this scattered cluster of coral islands – lying just 200 to 400 kilometres off Kerala’s coast – might soon become the next big testbed for India’s defence and technology ambitions.

For the Indian Air Force (IAF), Lakshadweep is more than a holiday destination. It’s a floating outpost – an “unsinkable aircraft carrier”, as defence experts like to call it – right in the middle of one of the busiest and strategic maritime routes in the world.

Nearly 80 percent of global seaborne oil trade passes through these waters. With growing geopolitical tensions, increasing narcotics trade, and expanding Chinese surveillance forays, establishing a strong operational base here is both a strategic necessity for India – and a logistical nightmare.

Operating in Lakshadweep is no walk in the park. The islands are tiny, the weather harsh, and the marine ecosystem fragile. Between June and October, when the monsoon hits, the place practically goes into isolation. Even basic supplies like onions and potatoes become hard to find. The rough seas and limited jetties mean ships can’t dock easily, and air transport is restricted to a single runway at Agatti. The other islands don’t even have space for one.

This isolation makes every box of supplies, every litre of fuel, a mini logistical hurdle. Traditional transport options like ships and helicopters are costly and unreliable in such conditions. That’s where technology – particularly cargo drones – comes into the picture.

Race to build: The Southern Air Command (SAC) of the Indian Air Force recently hosted an Industry Outreach Programme and Exhibition in Trivandrum (Thiruvananthapuram) titled “Over-the-Sea Cargo Drones for Logistics and Mobility Solutions for Lakshadweep and Minicoy Islands.” The event, jointly organised with the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), brought together defence officials, tech companies, and drone startups to explore how drones could rewrite the logistics rulebook for island operations.

The initiative also marked the launch of the fourth edition of the Mehar Baba Competition – a national-level challenge inviting drone innovators to develop high-endurance, heavy-lift prototypes for the IAF.

The brief is ambitious: develop drones capable of carrying a 300 kg payload, flying for five hours, and covering 300-500 km. Ideally, they should also support vertical take-off and landing (VTOL), given the lack of runways on most islands. In short, it’s not just about building a drone – it’s about redefining what Indian drones can do.

Looking Ahead: “If we have to protect these interests in these uncertain geopolitical times, it’s very important to continue developing these islands, both Lakshadweep and the Andamans. These will be our frontier posts in the future,” said Air Marshal Narmdeshwar Tiwari, Vice Chief of the Air Staff.

His words underline a larger vision: strengthening India’s island territories as strategic anchors in the Indian Ocean. Drones could be the glue that connects these distant dots – linking them with the mainland for supplies, surveillance, and emergency response.

But this is not just a defence story. Civilian life on the islands stands to benefit equally. Cargo drones could deliver food, medicines, and essentials even when ships can’t sail. They could also carry out search-and-rescue operations, monitor coral health, and provide rapid disaster relief.

Hurdles Galore: Of course, no breakthrough comes without its share of turbulence. For one, the conditions in Lakshadweep, like high humidity, salt-laden air, and strong winds poses serious engineering challenges. Drones must withstand “three highs”: high temperature, high salt, and high humidity.

Then come the legal and operational questions. What happens if a drone crashes into a fishing boat? Who’s responsible if it falls into a coral reef or damages marine life? And who owns the payload if it sinks? Before drones take flight, India must build a robust regulatory and liability framework to address such possibilities.

Startups are also seeking funding and testing support. As industry representatives pointed out at the event, even the winners of the Mehar Baba Competition must still compete in open tenders for contracts. That means heavy R&D investment without guaranteed returns. Developing long-distance drones with heavy-lifting capability presents even greater challenges.

“We may build a drone, but how are you going to fly it? Who is going to monitor it over the deep sea? Where will startups get accurate weather data during test flights?” asked Krishnamurthy H. K., Managing Director of Tamilan The Drone Private Limited. “The timeline for the challenge is about three years. I think we can do it in one year, provided there is proper funding and a support system.”

Air, Sea… or Both? There’s another interesting twist: what if the future drone doesn’t just fly, but also float?

Some innovators argue that India should explore amphibious or waterborne drones – vehicles capable of taking off and landing on both water and air. Such designs could bridge the operational gap between the Navy and the Air Force.

But that also raises the old question of turf: who governs the skies above the sea? Cooperation among the defence services will be key to ironing out such overlaps.

If done right, India could create a new class of dual-mode drones – something few countries have achieved.

The Global Race: India isn’t the only one chasing this dream. China has already made strides with the Boying T1400 – a Chinook-style unmanned helicopter developed by United Aircraft Technology. It can carry heavy loads across long distances and operate even in harsh conditions like the Himalayas and the South China Sea, according to the South China Morning Post.

Asian countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia – all with ongoing maritime disputes with China – are also in the market for long-range logistics drones. Many of them would prefer sourcing from India, given the security worry over Chinese-made drones. If Indian startups can deliver reliable, cost-effective models, the export potential is massive.

Beijing has doubled down on developing drones, joining the global race to create unmanned aircraft that can serve both civilian and military purposes. Reports have also pointed out that China has been operating unmanned underwater drone surveillance extensively in the region.

Beyond Lakshadweep: The latest IAF initiative isn’t just about one island chain – it’s about setting a precedent. Drones developed for Lakshadweep could find applications in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Purvanchal Hills in Northeast India, or even in disaster-hit coastal regions.

The technology could later be scaled up for civilian cargo delivery or humanitarian missions across the Indian Ocean Region.

At a broader level, it signals India’s shift from being a drone consumer to a drone innovator. The IAF’s open-door approach – working with startups, industry associations, and academia – marks a welcome departure from the old model of closed defence procurement.

A Sky Full of Promise: Lakshadweep’s isolation may soon turn into its greatest advantage. If Indian engineers and entrepreneurs can crack the drone code for these islands, they’ll be solving not just a local problem but a global one.

It’s a fascinating picture: quiet turquoise waters, coral reefs below, and sleek cargo drones humming above – bridging the gap between technology and geography.

For now, the race is on. And as India readies its next generation of drone innovators, one thing’s certain – the nation’s island outposts won’t be quite so remote anymore.

Chinese spacecraft snaps 3I/Atlas

Looks like this interstellar comet, 3I Atlas, is in disco mode. It started with a red hue, later appeared to be turning green, and now scientists say it is developing a bluish tint. The latest camera to snap a picture of our interstellar visitor is China’s Tianwen-1 spacecraft, which is orbiting Mars. China announced that it took a picture of the visitor between October 1 and 3, when it was 28.96 million kilometres away. Quite an achievement, given that it is a faint object moving at a velocity of 59 kilometres per second.

Another incident that caught the attention of space analysts and highlighted China’s growing space observation capability came when it reached out to the United States and asked Nasa for a space manoeuvre to prevent a possible satellite collision – the first time Beijing has made such a request. Nasa welcomed it and hailed it as an example of future cooperation. But it also indicates that China has a very effective space surveillance in place and able to track different orbits. This is something China had prioritised in its 2022 space White Paper, apparently to track space junk. Looks like they have completed that goal.

Maid in India, the instant version

One sector moving at warp speed in India is instant delivery. From food to groceries, you order it and get it within minutes. The latest to join that race is the delivery of domestic helpers. Bengaluru-based startup Snabbit, which recently raised nearly 80 million US dollars, says it plans to expand to more cities soon. The company offers trained personnel for cleaning, dishwashing, laundry, and kitchen preparation, with a database of thousands of skilled women. From 25,000 service calls in May earlier this year, Snabbit now receives up to 300,000 calls and expects to add another 100,000 by December. Most users are between 30 and 40 years old, including bachelors and working professionals.

Norwegian bus firms hit a bump

Transport companies in Norway and Denmark that have been using electric buses made in China by Yutong recently discovered that the manufacturer could remotely switch the buses off. Yutong says the access is for maintenance and software updates – part of its encrypted after-sales service, it told The Guardian. The catch: the company effectively has a kill switch that can stop the buses in their tracks. Yutong has sold thousands of such vehicles across Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the Asia-Pacific. At a time when Chinese EV makers are racing ahead globally, this isn’t exactly a glowing endorsement.

All roads that led to Rome

A team of researchers has just created a high-resolution digital map of roads from the Roman Empire – essentially a “Google Maps for chariots.” They pieced it together using old maps, photos, and satellite images. Meanwhile, back in Trivandrum, city officials are still trying to map underground drainage pipes laid just a few decades ago. The Romans had roads that lasted millennia; we have drains that vanish faster than the monsoon!